Geopolitics continue to take centre stage

The recent trend of U.S.-China relations becoming more fraught seems set to continue, yet with the possibility for new agreements as well as new disputes.

Active middle powers such as India, Russia and Japan will further complicate the environment for business, as will the ongoing toughening of the broader regulatory environment and activist stance of governments in directing economic activity to align with national goals, for example in critical minerals, semiconductors, electric vehicles (EVs) or batteries.

Trade-reliant economies such as Vietnam, Japan, Taiwan and South Korea will face uncertainty around market access.

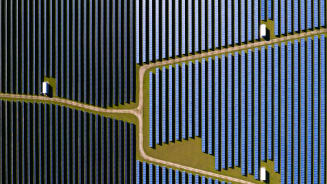

Asia Pacific supply chains are reshaped by geopolitics

For years, U.S. and Chinese firms have led the creation of new supply chains to reduce risk and take advantage of changing patterns of cost and technological capabilities, as well as developments in bilateral relations. For instance, over the last decade, the U.S. trade deficit has grown by 54 percent but the size of the deficit with Mainland China has shrunk.

India and ASEAN’s trade deficit has risen by a much larger than average amount. These new supply chains will likely face a changing regulatory environment in 2025.

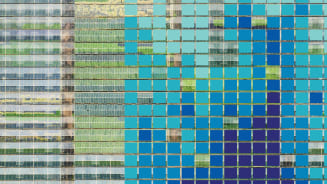

Underlying demand for Asia’s exports will continue to be heavily influenced by the AI-driven boom in semiconductors and related parts of the electronics industry. While the AI boom will likely moderate somewhat in 2025, regional exporters should still see good demand for their products.

Financial flows are following shifts in supply chains

As the U.S. Federal Reserve embarked on its rate-hiking cycle in recent years, most Asia Pacific currencies have depreciated, particularly consequentially in the large economies of Japan, Mainland China and South Korea. Both emerging patterns of cost differentials and regulation are driving investment, such as in production facilities in Japan, and sourcing of components cross border, such as China’s surging exports to Southeast Asia.

As the U.S. Fed continues to cut interest rates, any central bank holding rates constant or cutting slowly, such as in Malaysia or Thailand, should see currency appreciation. This will reduce export competitiveness even as it increases the spending power of local consumers.

So how will the region’s largest economies do in 2025? Asia Pacific will remain the world’s fastest-growing region, even as Mainland China’s economy slows against a mix of structural headwinds, such as a decline in the size of the workforce and weak confidence amid a property slump. Mainland China will be one of the few governments in the region embarking on fiscal stimulus rather than consolidation. This boost to spending could help to stave off deflation and manage a highly indebted property sector, making it countercyclical to much of the rest of the region.

Urbanisation remains the biggest driver of growth for Asia Pacific’s emerging economies and, combined with sufficient improvements to the business environment, will propel India, Vietnam and the Philippines to become standout markets for growth.

Significant numbers of new consumers are moving into the middle class, with implications for retail and travel, in particular. Demographic change is rapidly occurring, and economies like Thailand and Vietnam are going to face challenges with healthcare, pensions and employment due to ageing populations at lower levels of gross domestic product per capita than Mainland China did, and it in turn is facing them earlier than Japan or South Korea did.

Technological change remains a bright spot, with much of the global cutting-edge innovation, from semiconductors to EVs, taking place in regional economies.